The Significance of Women in the Recent Protests in Iran

In order to understand the recent protests in Iran, we shall consider the role of Iranian people's spontaneous protests, the opposition outside Iran and the great social and intellectual leaders both inside and outside the country. Of equal importance are the analysis of the regime’s reaction and the wavering opinions of politicians, celebrities and security forces over the course of the protests.

But we shall not neglect the important role of women who besides attending the protests bravely, as they always do in other protests and demonstrations, were shown in video footages to lead and encourage the protesters.

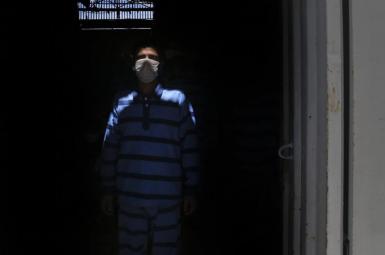

This led the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) to apply its cliché strategy of producing a false documentary to claim that women’s presence in the protests were organized by foreign forces. The documentary was aired last week in 20:30 News, yet it was hardly taken seriously by anyone. Nowadays, viewers are cognizant of the cooperation between IRIB and the Intelligence Ministry’s interrogators in fabricating staged confessions. Their strenuous effort, therefore, shows the regime’s failure to ignore the role of women in the recent protests.

The IRIB is notorious for falling back on trite narratives of uneducated prostitutes and runaway young women, ready to exchange their honor for a pittance, to soil the reputation of the women who attended the protests in an effort to silence them. This misogynistic practice is customary in retrograde and religious regimes like Iran. Violence against women does not always appear in the form of domestic violence or gender pay gap, though they continue being major problems in Iran. But the harshest violence against women is that of the regime when it uses femininity to discredit, oppress and weaken women and their civil and political demands; this violence goes unnoticed in forensic medical reports to international human rights organizations.

It is not difficult to count the numerous ways the regime applies violence against women, which are in accordance to the Sharia law: inheritance and child custody laws are biased against women; minimum age for marriage for girls has been reduced; an official permission by the father or a male relative is necessary for registering marriage; women who have extramarital relationships are stoned; Hijab is mandatory for all Iranian women; certain university degrees and professions are rationed based on gender; women are banned from entering sport stadiums- the list goes on. All these, which are justified as being tenets of Islam, signify the existence of official discrimination and the state violence against women.

It is worth mentioning that before the Islamic Republic was formed four decades ago, many of the above-mentioned restrictions did not exist. After the establishment of the Islamic Republic, the misogynistic Islamic laws were interpreted and executed to different degrees depending on whether power was held by a fundamentalist or a reformist government. As the women’s rights movement grew stronger and more experienced, activists gradually came to realize that different interpretations and varying degrees of executing the governing laws of the Islamic Republic do not contribute to the emergence of an equal society.

In recent years, especially over the past decade, as women’s communication with the world beyond the Iranian borders developed and levels of education and awareness rose and women’s movements and organizations became more active, it has become clear to Iranian women that the way to fight violence against women is not paved through crying and moaning in courts or trying to escape from their husbands or a criminal sentence through pleading to different media; rather, the way out is to fight the selfsame Law that endorses the violence against women. When its interests are involved, the regime has no qualms about using the Islamic law to silence women by threatening them with moral scandals; Islamic law is based on Islamic principles and thus possesses great executive power in any Muslim majority country.

November 25 was recognized by the UN as the international day for the elimination of violence against women and the ‘Orange the World’ campaign, lasting from that day until December 10, is an effort to eliminate violence against women.

Violence against women is allowed, executed and supported by Iranian law. Therefore, Iranian women have realized that in order to paint their world orange, they would need to leave these Islamic laws behind. By creating ‘an orange November’, Iranian women were witnessed not only as companions and members of the society, but they came to the streets as leaders to claim their rights through breaking taboos and fighting misogynistic laws.

In Eastern cultures, there is always a sacred aura surrounding a woman and therefore, an enlightened woman's invitation of other social activists and protesters to claim their civil rights can have a deep and great repercussion. Even after the protests die down, this woman ceases to be silenced and raises her voice as a mourning mother or sister and continues her fight for freedom. This is how numerous mothers have reacted to the deaths of their children, and instead of drawing back, they have gathered together to voice their and their children’s protest to the world they want to paint orange.

An orange world filled with civilized, happy and equal people is certainly a better place, provided that this color, a symbol of the battle against the violence against women, resonates with the heart and soul and especially the laws of every country.

Violence against women is generally understood in terms of disdain and humiliation of women and domestic, social and physical abuse; however, the worst and most dangerous form of violence against women is the systematic, misogynistic violence endorsed by religion. Nowadays Iranian women no longer seek punishment for an abusive husband, or employer or an acid attacker; they have realized that their demands, as humans and beyond gender, can only be met through targeting the source of this systematic violence and eliminating it. It is, therefore, clear why the IRIB drew nervously on its hackneyed scenario to introduce the women in the protests as uneducated or poorly educated individuals with no civil demands or grasp of the society’s situation. Nevertheless, even if we were to assume their proposition to be true, would these women be something other than the product of an unequal and abnormal society?

The call for an orange Iran has been an alarm for the theocratic regime, and it can certainly make a better Iran for Iranian men and women.