Profiles Of Iran's 2021 Presidential Candidates

Iran’s Guardian Council has disqualified all but seven of the 592 presidential hopefuls who have registered for the 2021 election. Such extreme vetting is not unusual for the Islamic Republic. Only eight and six candidates were permitted to run in 2013 and 2017, respectively. But its decision, which resulted in the disqualification of the longest-serving Speaker of Parliament since 1979 Ali Larijani as well as the sitting first Vice President Es’haq Jahangiri, raised eyebrows even among some longtime members of the Nezam (regime), including former Chief Justice and member of the Guardian Council Sadegh Larijani, who lashed out at the decision on Twitter. But with Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei supporting the Guardian Council’s decision in a speech to legislators on May 27, the presidential field has been effectively finalized.

Below are brief analytic profiles of the candidates whom the Guardian Council has qualified:

Ebrahim Raeesi:

Raeesi (Raisi) currently serves as chief justice of Iran. He has spent most of his career in Iran’s judiciary, starting out as a provincial prosecutor-general and later as chief prosecutor-general of Tehran, head of the judiciary's General Inspection Office, deputy chief justice, and then attorney general. He then left the judiciary and became custodian of Astan Qods Razavi, which is one of Iran’s most powerful religious foundations and economic conglomerates. While there he used the platform to mount an unsuccessful bid for president in 2017. After, he continued as custodian in Mashhad and was eventually tapped by Iran’s supreme leader to become chief justice in 2019. Soon after, Raeesi became deputy chairman of the Assembly of Experts--increasing his influence. While serving as chief justice, Raeesi has built his brand as an anti-corruption crusader. But his past—including serving on a death commission in 1988 which greenlit the executions of thousands of political prisoners—continues to cast a shadow over his career and will make him unpopular with voters attracted to reformist or more pragmatic candidates. That is not to mention his role in the crackdown on protesters during the unrest which followed the 2009 presidential election, when Raeesi was deputy chief justice. The US government later sanctioned Raeesi, citing these human rights abuses. During the 2017 campaign, President Hassan Rouhani issued veiled criticism of Raeesi’s record, saying that the “people of Iran are saying they don’t accept those who only hung and imprisoned people for the past 38 years.” This may emerge as a criticism of Raeesi in the 2021 election cycle as well, but his opponents may tread more carefully due to Raeesi being seen as a leading contender to succeed Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as supreme leader and because of Raeesi serving now as a sitting chief justice. The judiciary has systemically targeted allies of President Hassan Rouhani in recent years, and the other candidates will want to walk a careful balance. Khamenei has made no secret that he favors Raeesi as Rouhani’s successor, with his office recently releasing a poster outlining the qualities the next president should embody. “Pursue justice and fight corruption” is one of these qualities—a veiled reference to Raeesi’s status as head of the judiciary and the anti-corruption brand he has sought to build. During the campaign, Raeesi will likely stick closely to the supreme leader’s economic theories, focusing more time on creating a resistance economy and boosting domestic production than on negotiations with the West. If elected, Raeesi will become the first chief justice of the Islamic Republic to ascend to the presidency and has the potential to be a consequential chief executive given Khamenei’s old age.

Abdolnaser Hemmati:

Hemmati, in contrast to Raeesi serving as a religious and political leader, is a technocrat without a natural political base. He recently was the governor of Iran’s Central Bank, having been named by the Rouhani administration to his post in 2018. On May 30, 2021, Rouhani removed him from the governorship due to Hemmati’s presidential run. Previously, he served a short stint as Iran’s ambassador to China; president of Iran Central Insurance and head of the Insurance Supreme Council; chairman and CEO of multiple major banks including Bank Melli, Future Bank, and Bank Sina; a member of the economic committee of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC); and vice president of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), among other posts. Thus, Hemmati’s career has been spent steeped in the banking sector. He does have some international and security experience—Hemmati has often led delegations to countries to resolve banking disputes and has exposure, albeit limited, to the inner workings of the SNSC, over which he would nominally preside as president. He will likely showcase his economic prowess and offer a contrast with other more ideological candidates—after all he has received plaudits for privatizing the insurance sector. Hemmati also has a history of parachuting into positions to help scandal-plagued institutions recover. Hemmati landed at Bank Melli in 2013 after its former chairman Mahmoud Reza Khavari fled to Canada in 2011. Khavari was tried in absentia in a massive embezzlement case. Hemmati was also elevated as governor of Iran’s Central Bank after Rouhani fired Valiollah Seif amid a mounting economic crisis following the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal in 2018. Seif was later indicted for mismanagement of more than $30 billion and 60 tons of gold reserves. Despite not having any previous political experience, Hemmati will likely seek to attract the Rouhani coalition of reformists and pragmatists. But voters will likely be demoralized given the mass disqualifications of the Guardian Council. This is not to mention that Hemmati’s association with the Central Bank could prove to be a stumbling block for his candidacy and offer material for his rivals to use against him given the poor economic condition of the country and the unpopularity of the outgoing Rouhani administration.

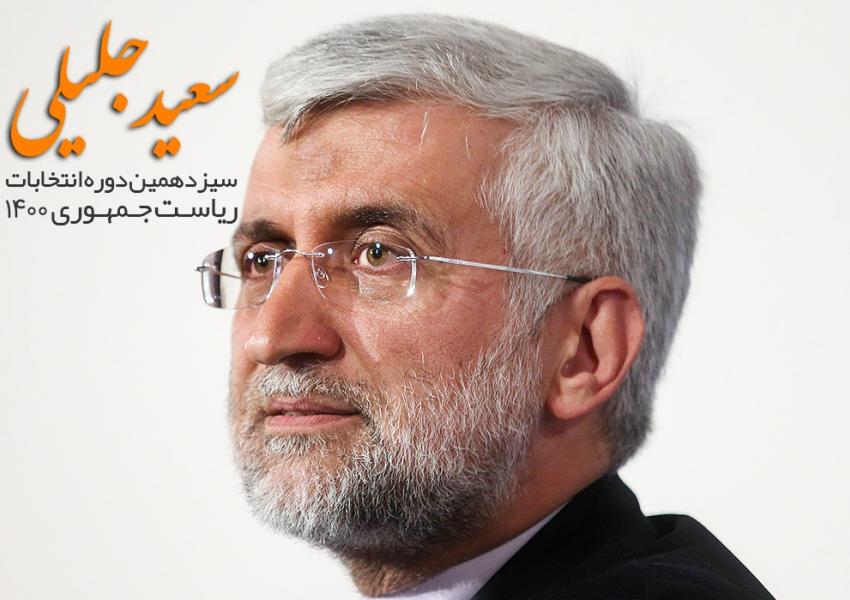

Saeed Jalili:

Jalili has served as a loyal Khamenei disciple for decades. A veteran, he was injured during the Iran-Iraq War in Operation Karbala 5 with his leg having to be amputated as a result. Jalili’s thesis at Imam-Sadegh University focused on “foreign policy of the Prophet,” where he was a pupil of Ayatollah Ahmad Alamolhoda, the father-in-law of Chief Justice Ebrahim Raeesi. He joined Iran’s Foreign Ministry in 1989 at the dawn of Ayatollah Khamenei’s supreme leadership, where he became deputy foreign minister for Euro-American Affairs. In 2001, Jalili transitioned to the Office of Iran’s Supreme Leader, becoming senior director for policy planning. This provided important exposure to both Iran’s elected and deep states. An advisor to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at the beginning of his presidency, Jalili eventually succeeded Ali Larijani as secretary of the SNSC, which once again positioned him at the center of the national security hierarchy while also functioning as chief nuclear negotiator. Jalili used the post as a springboard to run for the presidency in 2013. Audiences greeted him on the campaign trail as “a living martyr.” Headlines identified him as Khamenei’s “protégé” and cast Jalili as the “establishment’s favorite to win.” But he lost the race, coming in third place and receiving only 11.4 percent of the vote. Nevertheless, Khamenei found a landing spot for Jalili, appointing him as one of his representatives on the SNSC. Counting his time as secretary, this means that Jalili has served for over a decade on the SNSC itself. Despite this long tenure, he is likely to come under criticism from more pragmatic and reformist figures in the race over his time as chief nuclear negotiator under Ahmadinejad’s administration. Rouhani at a recent cabinet meeting quipped “whether you want it or not, this government has been successful in every negotiation that it had in the past eight years, while some came back from every negotiation with a resolution against the country.” Jalili will also be overshadowed by bigger names like Raeesi given the overlap in their conservative constituencies. But he may be able to run reinforcement for the chief justice during the presidential debates, as first Vice President Es’haq Jahangiri did for Rouhani during the 2017 election. If he loses, Jalili may still have his eye on a seat in a Raeesi cabinet.

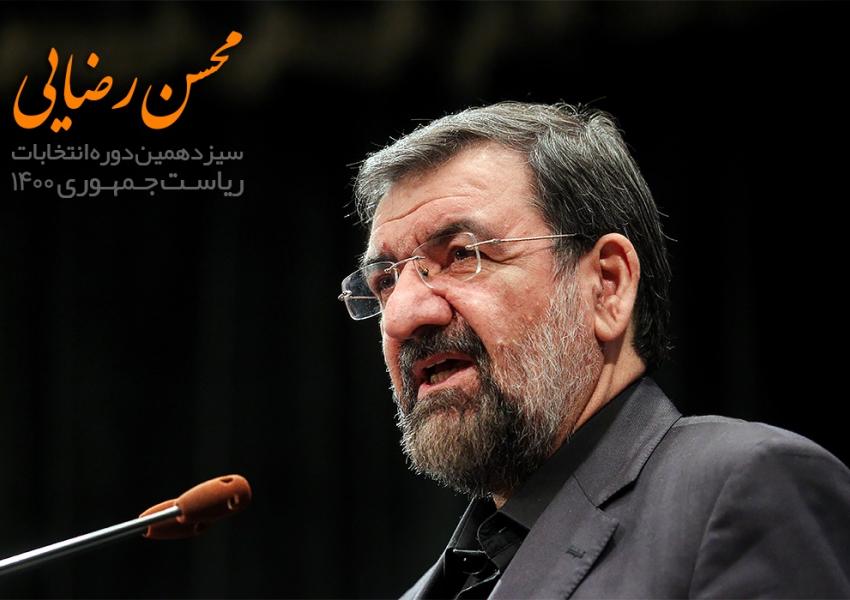

Mohsen Rezaei:

Rezaei has been a perennial presidential candidate—in the 2005, 2009, 2013, and now 2021 cycles—but he has lost every election he has ever contested—both for parliament—in 2000—and the presidency. More broadly, he served as commander-in-chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) from 1981-1997, leaving office upon the election of Mohammad Khatami as president. Khamenei decided to replace Rezaei with Yahya Rahim Safavi after Rezaei dabbled in politics during his tenure at the helm of the IRGC, supporting Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri in the election against Khatami. The supreme leader then named Rezaei as secretary of the Expediency Council, which adjudicates disputes between parliament and the Guardian Council, and advises him personally. Rezaei has used this position as a political platform for himself since 1997 to launch multiple unsuccessful attempts to hold elected office. During this time, Rezaei has been a headache for Khamenei, especially after his son Ahmad Rezaei left Iran for the United States where he spoke out against the Islamic Republic, but then returned years later and was found dead in a hotel room in Dubai in 2011. Rezaei returned to the IRGC in 2015 after Khamenei granted him permission to do so, with a teaching position at Imam Hossein University. Soon after he registered in the 2021 election, reports circulated that he had a health condition that the Guardian Council was evaluating, which prompted the 66-year old Rezaei to release a video showing him running and playing soccer. With Khamenei looking for a young and Hezbollah government, Rezaei’s candidacy looks like a placeholder to create the illusion of competition in the race.

Alireza Zakani:

Zakani is the hardline head of the Parliament Research Center and a former legislator from 2004-2016. A physician with a degree in nuclear medicine, Zakani also served as the head of the Student Basij Organization. He has been owner of Jahan News as well as secretary-general of the Alliance of Wayfarers of the Islamic Revolution. Zakani, who was an early supporter of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, eventually used Jahan News as a cudgel against Ahmadinejad’s excesses, particularly lobbing corruption allegations against senior Ahmadinejad officials. Zakani played a prominent role as a legislator, serving as the head of the parliamentary commission on the nuclear deal. He was a critic of the Rouhani administration’s nuclear negotiations with the P5+1. For instance, Zakani spearheaded a letter to the president in 2015 complaining about the deactivation of centrifuges which legislators claimed contravened the orders of Iran’s supreme leader. Despite Zakani’s leadership role in parliament, he was disqualified from running for the presidency in both 2013 and 2017. After the election of a conservative-dominated parliament in 2020, Zakani was named as the head of the Parliament Research Center. He used the position as a platform to espouse maximalist demands as the Vienna talks on reviving the 2015 Iran nuclear deal took place, with a report from the Parliament Research Center claiming that verification of U.S. sanctions being lifted would take three to six months—a substantially longer period of time than Iran’s president and foreign minister indicated in public. They suggested verification could be done quickly. Zakani’s bid will appeal to conservatives—especially after he was barred from running twice—but his chances of mounting a successful candidacy for president against Ebrahim Raeesi remain very low. As others have done during past Iranian campaigns, Zakani could leverage his campaign to secure a position in a Raeesi cabinet, should he win the presidency.

Amir-Hossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi:

Ghazizadeh Hashemi is a longtime legislator, who currently serves as the first deputy speaker of parliament. A surgeon and ENT specialist by training, Ghazizadeh Hashemi has been a member of parliament since 2008. He is a member of the Front for Islamic Revolution Stability and previously was the principlist party spokesman. He has called for a “dialogue between the administration and the people” with a campaign theme of “the administration of Islam.” He holds extreme positions on the nuclear file, and has previously advocated for withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty if Iran’s case is referred to the U.N. Security Council and has been a senior leader of the legislative chamber as it passed a nuclear law which gradually escalated Iran’s nuclear program to force the United States to return to the nuclear deal. As with other candidates in this cycle, Ghazizadeh Hashemi will face stiff competition for the conservative vote from other figures in the race, most especially Ebrahim Raeesi, Alireza Zakani, and Mohsen Rezaei. If he loses or withdraws, Ghazizadeh Hashemi could potentially have his eye on a cabinet position or another assignment.

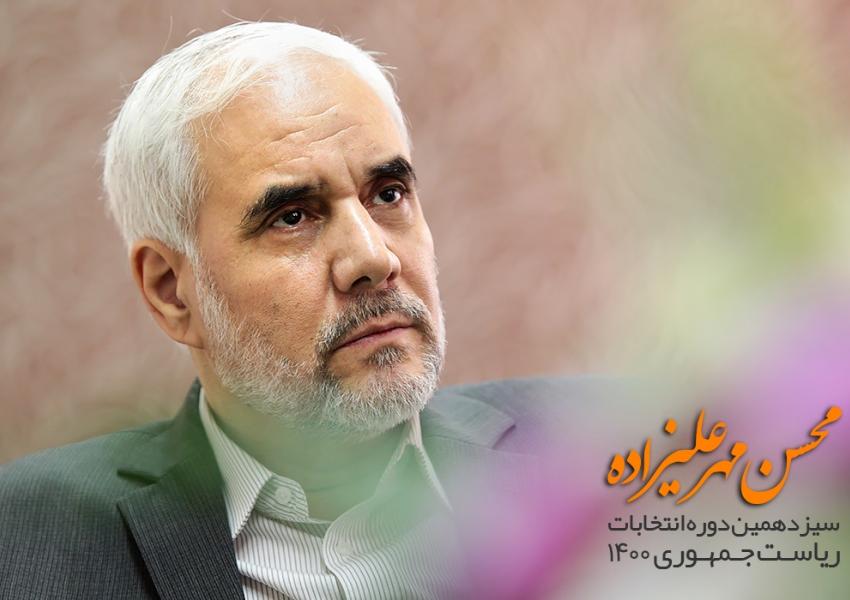

Mohsen Mehralizadeh:

Mehralizadeh has been a longtime reformist politician. His previous positions spanned the Rafsanjani, Khatami, and Rouhani presidencies. An engineer by training, Mehralizadeh served as director of the Kish Free Trade Zone, a senior official at the Atomic Energy Organization in charge of power plant affairs in the 1990s, as governor-general of Khorasan Province, vice president and head of the Physical Education Organization, chairman of the Tourism Commission at the Tehran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines, and Agriculture, and later as governor-general of Isfahan Province during the Rouhani presidency. In 2005, Iran’s supreme leader made an extraordinary intervention into the presidential race, which resulted in the Mehralizadeh receiving approval to run for the presidency after the Guardian Council previously disqualified him. But he performed poorly during the 2005 contest, receiving the lowest number of votes. At one point, Mehralizadeh emerged as a candidate to become mayor of Tehran, but the Tehran City Council wound up choosing someone else. In the 2021 presidential contest, Mehralizadeh faces tremendous obstacles. In addition to lacking name recognition, he lacks the institutional advantages that the other candidates bring—all are members of the Islamic Republic’s establishment, with Raeesi as chief justice, Hemmati as the recent governor of the Central Bank, Jalili as a representative of Iran’s supreme leader to the SNSC, Rezaei as secretary of the Expediency Council, Zakani as head of the Parliament’s Research Center, and Ghazizadeh Hashemi as a deputy speaker of parliament. This is not to mention that leading reformists, specifically the Reformist Front, are refusing to back any candidate due to the Guardian Council’s mass disqualifications. Thus, with Mehralizadeh failing to attract votes of confidence from even his own faction, he is likely there to serve as a token reformist in an uncompetitive race.