A Former Syrian Political Prisoner Recalls Jail Conditions

“When I get rid of the millions of volts I received in my body while shocked by electric tasers daily for months by Air Force Intelligence…When my knees and ankles joints are healthy again. When my broken teeth that I lost are back in my mouth. When the scars of torture on my body disappear. I would call that a level of justice.”

In an interview with Iran International, Mansour Omari insists this cannot happen: “Time will never go back to before I was tortured or bring back the lives of those who were killed under torture.’’

Omari began documenting the ‘disappeared’ in Syria during the 2010-11 ‘Arab Spring’ for the NGO Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression. This led to 356 days in jail from early 2012.

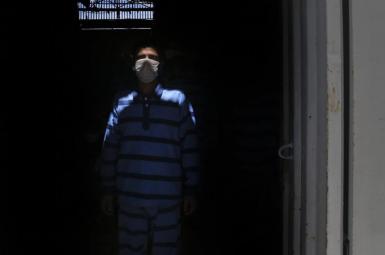

He recalls a military detention center, where he spent much of the year. With three floors underground, there were no windows, and no access to exercise. Between 60 and 80 cellmates were squeezed into a bug-infested room of 25 square feet, with one tiny dim light. Prisoners took turns standing, crouching, sleeping, and sharing a toilet.

Areas Of ‘Safety’

Omari’s current concern is Denmark’s recent decision to strip residency permits from 94 Syrian refugees, endangering around 500 others from Damascus and Rif Damascus, areas of Syria deemed “safe” by Danish authorities.

“This…mocks Syrians who fled for their lives”, Mansour wrote recently in the Al-Araby newspaper. “Thousands of Syrians cannot see the sun because they are held in Assad’s underground detention facilities… the Assad regime is still committing atrocities …Hundreds of thousands are still missing, many in detention and torture.”

Omari’s story was in 2018 told by the documentary film ‘82 Names: Syria: Please Don't Forget Us,’ directed by Iranian-Canadian Maziar Bahari.

The film highlighted Omari’s collection, while in jail, of the names of fellow detainees. He drew help from his four cellmates, among them, Nabil Shurbaji, another journalist, who had the neatest handwriting.

Blood And Rust

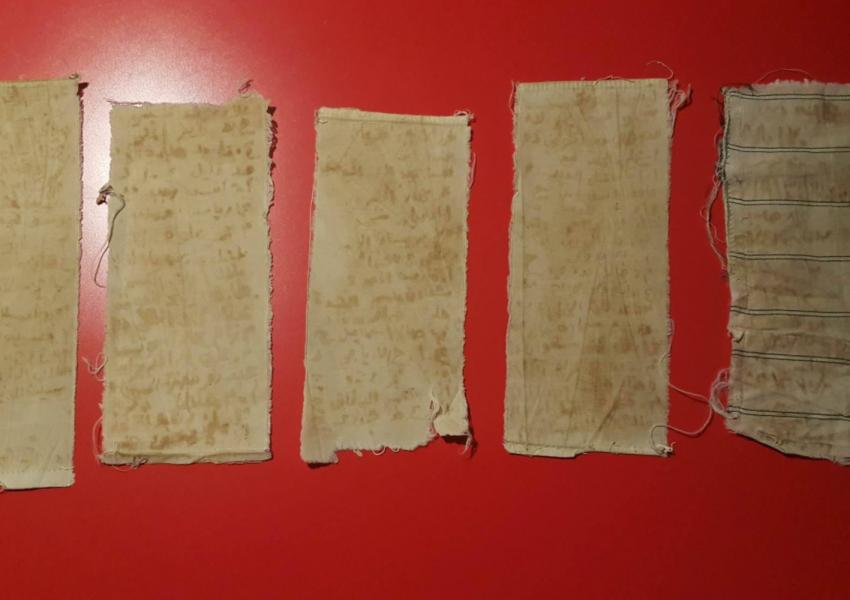

They lacked paper and pens. But one prisoner, a tailor, squeezed blood from his gums swollen with malnutrition, filling a plastic bag. Mixed with rust, it became an ink. Five precious scraps of cloth served as paper.

Names of 82 prisoners were hidden in the collar and cuffs of one of Shurbaji’s shirts until the day Omari was called for transfer to Adra prison, north-east Damascus. Tugging on the shirt in haste, Omari kept the names through two prisons until his release in February 2013.

“Every time I open the box that contains the cloth of the names with blood and rust, it’s like I open a casket,” Omari says. “It is like opening a grave…bringing back all the memories, their faces, voices and stories, the sufferings, the torture, the shouts and abuse of the torturers.

“However, whenever there is a chance to tell their story I will not hesitate. I will keep the box open for the world to see. Till one day we know what happened to all of those on the list and hold the perpetrators accountable. Only then, can I get some relief.’’

Omari has dedicated his life to his promise to fellow detainees to tell their stories. Of the 82, the fate of only 11 is known. 6 of them died in detention, the latest is an engineering student.

A Swedish citizen since 2018, Omari has written widely, including in the New York Times and the Daily Beast. He is a Syrian consultant for Reporters without Borders, while his 2015 book Syria Through Western Eyes offered a critique of reporting on the Syrian conflict.

Road To Recovery

Omari’s story is also one of recovery, albeit slow, and he has recently begun counseling offered by Amnesty International. “When I first arrived in Sweden I was sent to an area where there were [sic] no psychologists available, the closest one was 12 hours away by train,” he says. “However, treating myself was not my priority, as I was motivated to work for those whom I left behind in detention.”

Charles Lawley, communications chief at Syria Relief, a UK charity formed to support victims of the Syrian civil war, says there is little help for traumatized people within Syria.

“Unfortunately, in the case of Syria, research on the impact of trauma is still relatively new, whilst causes of trauma - namely violence - are still happening,” Lawley says. “As there are very few outlets for Syrians, especially IDPs [internally displaced persons] and refugees, to receive mental health support, many are forced to have their symptoms untreated and live with their trauma.”

Syria Relief and other NGOs do offer services within Syria, but these are dwarfed by demand. Plus, Lawley says, Syrians are largely unaware that support is available. “In our study of IDPs in Syria, we found that 99 percent of respondents had PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] symptoms but only 1 percent were aware of mental health services available to them.’”